Teaching Biology…

- Things Education

- Aug 29, 2025

- 7 min read

...through inquiry-based learning.

Hello all. Welcome to the 129th edition of TEPS Weekly!

Recently, we came across a 20-year-old research paper. This study asked a simple question: Would students understand genetics better if we moved away from lecturing and tried an inquiry-based approach instead?

A group of 45 ninth-graders was split in two. The first control group learned genetics the usual way – teacher explained, students listened, and the textbook was the main guide. The second experimental group learned through inquiry. They worked in small teams of four. Instead of a textbook, they used specially designed worksheets with short readings, diagrams and mini-investigations. The teacher stepped into the role of a facilitator, guiding their work rather than giving answers. Each topic began with a real phenomenon or data set. Students observed, asked their own questions, analysed tables, diagrams and charts, checked their predictions against the data, and then shared and defended their conclusions with peers — just like scientists do.

Both groups were tested before and after the unit on their understanding of DNA and inheritance (how traits are passed on from parents to children). The post-test had two parts. Part A asked recall questions such as definitions and simple explanations. Part B asked conceptual questions that required students to link ideas – for example, making connections between structural components like DNA and functional components like inheritance.

Pre-test: No significant difference between groups—this means that all students started with the same level of prior knowledge.

Post-test: Both groups improved significantly after instruction.

The experimental (inquiry) group outperformed control:

In Part A (basic, recall-type questions), both groups improved similarly.

In Part B (higher-order understanding), the inquiry group scored significantly higher.

Both groups improved. But the inquiry group scored much higher on questions that demanded deeper conceptual understanding. This tells us something important. Students need to see how ideas connect – like the inquiry group did, by analysing data and linking structure and function.

There has been a lot of debate on the merits, or lack thereof, of using inquiry in learning science. But biology is a bit different. Unlike physics or chemistry, which are often about universal laws, biology is full of nuance and variation. For example, a whale looks like a fish but is actually a mammal. Here, deeply understanding how to classify it is more useful than just memorising lists of animals. There is so much information in biology that trying to remember it all can feel overwhelming and boring. But when students explore and investigate, like in inquiry-based learning, they understand more deeply.Despite this, biology is taught in a way that students settle for neat, simple answers, even if those answers hide the real complexity. Saying “a whale is a mammal” is a neat answer, but the real complexity lies in understanding how we classify animals. Understanding why even though a whale ‘looks like’ a fish, it is a mammal. This is where inquiry, which includes opportunities for cognitive conflict and active thinking, is important in biology.So how does one use inquiry to cause cognitive conflict and make students think actively? Let’s dive in with an example from a forensic science class:In one of my classes, we introduced a case where saliva was one of the pieces of evidence. The task was to solve the case by analysing DNA. I could hear students saying things like:

“Oh! Saliva will have DNA!”

“DNA is specific to a person!”

“No two people have the same DNA!”

“Only identical twins have the same DNA!”

“We just analyse the DNA!”

All of these were true. The learning outcome was for students to be able to explain how the DNA of one individual differs from that of another.

So, we paused the casework and started with what they already knew. We made a quick list on the board: DNA is in the nucleus, within a cell; it has a long, twisted ladder shape; it holds instructions for the body.

At first, they were confident. Then I asked them to think more deeply: what exactly in DNA holds instructions? Now, there was silence. They realised they had never looked at DNA from that angle before. They thought they “knew it all,” yet they could not answer something that seems so simple. We wrote this question on the board as our inquiry question.

To prompt them more, I asked: “The DNA in the cells of my feet must be different from the DNA in the cells of my forehead, right?”

They unanimously said, “Yes. They are different because these parts have completely different features.”

“Aha! Misconception!” I thought. So, I followed up: “But you said all humans have unique DNA. If my feet and forehead DNA are different, then would they still belong to the same person?”

Now that we had a broad question that broke their belief, they were primed to inquire and learn more about it. Now, here is how we used this misconception as an inquiry way – We broke down our broad question further:

Is DNA the same across all body cells?

What part of DNA makes one person different from another?

How do scientists see or analyse those differences?

First, we tackled the question: Is DNA the same across all body cells?To explore this, I asked a student to come to the board and draw a cell from the foot. Then another student drew a cell from the forehead. We compared them. Both drawings had the same main parts: a cell membrane, cytoplasm and a nucleus.

They could see that a cell is a cell no matter where it comes from. The cells had the same parts - cell membrane, nucleus, etc. However, I showed them images of nerve cells, then liver cells, then skin cells. Here the students quickly noticed that the parts of the cell remained the same, but there were multiple differences between how the cell looked. The nerve cell had a cytoplasm that was different in shape - main body and a long tail-type thing.

I then added: “Just as both cells have the same parts, the DNA in the nucleus also the same across cells, however something is different to give very different structure and function to each type of cell. What does that suggest about the difference in DNA?”

They all said, “The DNA is the same! But something makes different cells different.”

One student jumped and said, “The DNA is the same, but their instruction to the cell can be different.”

This point nudged them to start connecting structure and function to the bigger idea.

The conversation continued, with some clinging to “different” because body parts look different, but gradually they saw the evidence stacking up for “same.” Every “body cell” — what we call somatic cells — has the same DNA. What makes a foot cell different from a forehead cell is not that the DNA is different, but that different instructions from the DNA are being “switched on” in each place. They discussed, debated and concluded that DNA is the same everywhere.

Then we moved to the next big question: What part of DNA makes one person different from another?

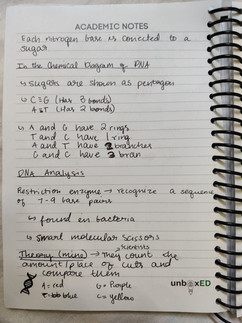

We began by going back to the structure of DNA. On the board, students drew the double helix — the twisted ladder. They labelled the backbone and the rungs made of nitrogenous bases like A, T, C and G.

They concluded that these bases form long sequences for the DNA like: ATCGATCGATCG…

I asked: “Now that you know what DNA contains, if DNA is the same in all your cells, then what makes your DNA different from mine?”

To find out, I gave each group paper strips with short DNA sequences. Most of the sequence was the same, but there were tiny changes.

Person A: ATCGATCGATCG

Person B: ATCGGTCGATCG

Person C: ATCGATCGTTCG

Students put the strips side by side and circled the differences. They quickly noticed that although most of the letters matched, the small differences were enough to tell one person’s DNA from another’s.

Finally, we asked: How do scientists actually see or analyse those differences?

I told the class, “DNA is too long to look at directly. Suppose scientists use something like tiny scissors, called enzymes. These enzymes cut DNA at specific sequences. If we treat two different DNA with these enzymes, what will happen?”“Both DNAs will be broken down into pieces”

I asked, “Then will there be any difference in those pieces?”“Because each person’s DNA is slightly different, the scissors will cut at different points. That means the DNA breaks into pieces of different lengths for each person.”

To model this, I gave each group simple DNA band patterns on paper. One was from the crime scene saliva, the others from three suspects. Students had to line up the patterns and find which one matched.

As they worked, they noticed that each person’s DNA pattern looked a bit like a barcode — bands of different sizes lined up on the page. When they matched the crime scene pattern with one suspect’s pattern, it all came together:

DNA is the same in all cells, so saliva DNA is as good as blood or hair follicle.

People differ because of small changes in their DNA sequence.

Scientists use molecular scissors to cut DNA into fragments.

These fragments create a band pattern when separated.

Matching patterns show that two samples come from the same person.

By the end, the students weren’t just saying “DNA is unique.” They could now explain how DNA helps scientists identify a person.

And here’s the crux of it: the misconception wasn’t just corrected by the teacher telling them. It was discovered and then resolved by the students themselves.

In Mathematics and other natural sciences, like Physics and Chemistry, the focus is often to find general proofs or laws that hold true everywhere. Biology is different. It is full of variation and exceptions. Knowing just facts on their own can feel disconnected. “DNA gives instructions to the body. It is unique to an individual.” is factually correct, but in isolation, it means very little. In the context of biology— a science of variation—it has a lot to it: DNA is the same in all cells of one individual, but different instructions are given in different parts of the body. At the same time, small differences in DNA between individuals are what make one person different from another.

That is why inquiry in biology classrooms is important. The goal, then, is to shift from facts in isolation to concepts in context to building connected ideas. By starting with questions that unsettle and puzzle (i.e. create a cognitive conflict), we create space for misconceptions to surface. And when students investigate, argue and resolve those misconceptions, that is when true understanding begins.

If you found this newsletter useful, please share it.

If you received this newsletter from someone and you would like to subscribe to us, please click here.

Edition: 4.36

Comments